Shortly before Christmas, The Economist, the world’s leading news magazine, published an article titled “The liberalisation of Ireland,” with the subheading “How Ireland stopped being one of the most devout, socially conservative places in Europe.” This has been a familiar discussion both at home and abroad, particularly after the landslide vote to legalise abortion in 2018.

The Economist’s piece provides a brief overview of recent social milestones, followed by a description of physical and sexual abuse by clergy or within Church-run institutions. Although some conservative voices are quoted, the article presents a narrative which is endemic in modern Ireland: the theocracy of yesteryear has been destroyed, and Ireland has been born anew.

“In an angrier world Ireland has a lot to teach people,” one of the leading activists is quoted as saying. At a time when growing nationalism and populism is threatening the worldview of cosmopolitan Economist readers, Ireland has suddenly developed into a poster child for liberal values. The country’s politicians are very eager to assert this newfound identity at home and on the international stage.

But this article does not provide a thorough enough explanation of how “The liberalisation of Ireland” occurred, or what it means for Ireland’s present or future.

The world turned upside down

There is one thing which the article notes that cannot be disputed. Over the last few decades, the position of the Catholic Church in Ireland has changed beyond recognition. Admittedly, almost 80 percent of the population still identify as Catholic, and with about one in three Irish people saying they attend weekly church services, we remain one of the most church-going nations in Europe. Yet the residual influence of Catholicism in Irish life does not mask the collapse which has occurred, and which will likely accelerate.

Church attendance has fallen dramatically in recent decades. Church congregations are larger in Ireland, but they are also greyer than elsewhere, and there is a more pronounced generational divide. As older people die off, Mass attendance rates in Ireland (already as low as 2 percent in some Dublin parishes) will soon resemble those in even more secular countries.

Vocations to the priesthood plummeted decades ago and are not recovering. A sign of the problem can be seen in recent figures showing that four times more men were studying for the Catholic priesthood in England and Wales than in Ireland. The real significance of this trend will be seen in the coming years, when huge numbers of Irish parishes will likely be without a parish priest.

Apart from falling numbers, the influence of the Church in public life is probably going to diminish. Fresh from their victories in redefining marriage and stripping legal protection from the unborn, liberal campaigners are now focusing on efforts to force Catholic schools and schoolteachers to violate their ethos in areas such as sex education, or better yet, attempts to nationalise and secularise Catholic schools. The predominant feeling of the average believing Catholic in Ireland is often one of wearied acceptance.

The battle is over, and it is lost.

Catholicism by convention, not conviction

How did this happen so quickly? The Economist puts forward several explanations, none of which is entirely convincing.

The writer begins with a contrast between an octogenarian practising Catholic Agnes, and her 27-year-old Síona Cahill. Síona works for the Irish Family Planning Association, an abortion provider and advocate.

It looks like a straight-up contrast between the old Ireland and the new Ireland.

But it quickly becomes clear that the contrast between the two is not so great at all. Though a daily Mass-goer whose life “still resolves around the Church,” Agnes voted to legalise abortion, and even joined her granddaughter in canvassing for the removal of the right to life from Ireland’s Constitution.

No questions are posed to the old woman about how she reconciles belief in Jesus Christ with support for ending the lives of unborn children. That is to say if she does believe at all. For many older Irish Catholics, regular Mass attendance has little to do with religious faith and more to do with routine, a routine which a few generations ago attracted virtually the entire Irish population to church each Sunday morning.

For a decent-sized minority, Mass has long been as much a social outing as it is anything else, where people (especially those living in the countryside) come together to discuss the local goings on before the service begins, and as soon as it ends. The sense of being part of a shared community of faith is not felt as strongly during Mass in an Irish church as it is in England for example, where Catholicism is less common but in a much healthier state.

During and after the referendum campaign, many Catholics bore witness to this in their local parishes. Faced with many unbelieving parishioners, many priests stayed quiet in the run-up to the abortion referendum, just as they stay silent on all other contentious Church teachings. The results of this were seen in the fact that 66 percent of Irish voters said “Yes” to abortion-on-demand. Such a figure could not have been achieved had several hundred thousand practicing Catholics not supported the move.

Agnes was not alone, by any stretch.

Those of her generation were born into an Ireland where nominal Catholicism was for historical reasons part of our national identity. There was no real challenge to the Church on a political level after the English abandoned sixteenth and seventeenth century efforts to enforce Protestantism on their first and most troublesome colony.

After independence, politicians of the fledgling Irish state sought as close a relationship as possible with the hierarchy, with the result that clericalism took hold. A Catholic state emerged, one where – as James Joyce once said – Christ and Caesar were hand in glove. Naturally, complacency set in. The question of “Why do we believe?” was not often asked and required no great consideration.

Without a case against being Catholic, few ever had to consider the case for the Faith.

Compare this with the experience of other European Catholics. In France, for example, believers have had to contend with an anti-clerical state on and off since the Revolution, and a much stronger Catholic identity exists there, albeit among a small minority. In contrast, Ireland remained almost uniformly Catholic for much, much longer. But the collapse, when it came, was all the more dramatic.

Why did this happen so quickly?

The possible explanations for why this “social revolution” which The Economist puts forward are to some extent unconvincing.

“Exposure to the outside world” and increased foreign travel form one suggestion, and this has some truth to it, given the similar social trends which have occurred here and elsewhere in the West.

But Ireland was controlled by a foreign – and expressly anti-Catholic – country for centuries and remained stubbornly Catholic.

More importantly, the country’s experience of mass emigration dates back to the Great Famine in the mid 1800s, more than a century before the process of secularisation began. At a time when most Irish families had friends and relatives in non-Catholic countries, the country remained observant, as did Irish immigrant communities in Britain, America and further afield.

The author rightly suggests that the sexual abuse crisis is a reason why the drift away from Catholicism here accelerated. This is certainly correct, but the timeline shows that this was not the primary cause. The most damning and damaging official investigations into abuse in Irish dioceses or Church-run institutions were published in the last fifteen years. This is long after the shift away from Catholicism had commenced.

A new kind of conformity

Again and again, it is suggested by The Economist that the dramatic changes in Ireland are a result of normal Irish people beginning to speak out about the past and present. The impression given is of an Ireland where a stultifying silence has been replaced by a diversity of opinion, with the result that the country has now chosen secularism en masse. But as the Catholic journalist Breda O”Brien notes in the article, a strong “conformist streak” is present in the Irish character.

Modern Ireland is a place where there is remarkably little debate about public or social policy, and the body politic tends to move in unison, rather than diverging on left-right lines as occurs elsewhere. This, more than anything else, allows for rapid social change. The two main political parties in Ireland, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, are of a centrist disposition, with Sinn Féin and the remaining smaller parties being left-leaning. Up until the last general election in 2016, Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin were all ostensibly pro-life, but by the end of 2018 all three parties had come to support the Government’s abortion legislation, with all three party leaders doing an about face in renouncing the pro-life views they had so recently espoused.

Similarly, there is no significant ideological divide in the country’s media, with all of the major newspapers adhering to a liberal viewpoint on social matters. Ireland’s State broadcaster RTÉ occupies a disproportionate role in the media landscape and is well-known for its liberal bias, particularly when it comes to how it deals with Catholicism and how it depicts the past.

In these circumstances, and absent any substantive public debate, it is easy to see why a recently secularised country, embarrassed by its past and desperately seeking a new identity, would latch on to a role as an exemplar of liberal values.

What can be done?

For beleaguered Irish Catholics struggling to comprehend this new Ireland, there is little hope of the situation changing in the short term.

That does not mean that all hope is lost, though.

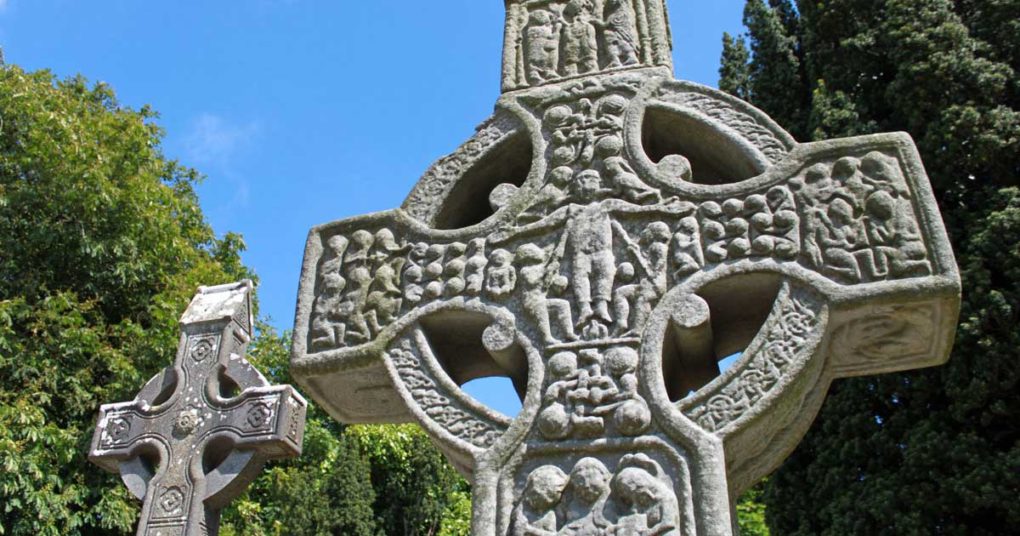

A first step in challenging the prevailing consensus is to tackle the deliberate misrepresentation of the past, which is so frequently the starting point for a campaign to usher in damaging changes in the present. The Church needs to focus more on reminding ordinary Catholics of the enormously positive role it has played in the 1,600 years since the coming of St Patrick: the story of Irish scholars and martyrs, the history of our missionaries, the good work done in our schools and hospitals, and so on. Because as long as Catholic Ireland is being maliciously depicted as one long abuse scandal, there is little prospect of lapsed Catholics being drawn once more to the Faith.

Another crucial step now is recognising that there is no point in fighting worthless battles for the broader culture. Religious orders are gradually withdrawing from hospitals in which the lives of unborn patients are being taken daily. This withdrawal should be finalised without delay.

Similarly, a unilateral withdrawal from the majority of Catholic schools, and the consolidation of a distinctive Catholic identity within the remaining schools, would be better than seeing Catholic education die as a result of a thousand cuts.

Secularists often bemoan the presence of religious oaths for political or judicial offices, and references to God in the Irish Constitution. Rather than fighting a futile campaign to preserve the remnants of the Church-State model which has damaged the former party so badly, the Church should get out ahead of its opponents and formally request that these references be removed.

A Constitution which now makes specific reference to the killing of unborn children should say nothing about “our obligations to our Divine Lord, Jesus Christ.” Liberal and anti-Catholic voices have long demanded a secular state in Ireland. They should be given it. And modern Ireland should be made to own its many failures without any opportunity to blame Christianity.

Here too, there is hope. Christians throughout the Western world are facing the same challenges in a post-Christian environment, but in other countries believers have had longer to adjust to the new reality.Catholic Ireland is in this respect – as its critics like to say – behind the times.

But with the right leadership, we might just wake up.

About the Author: James Bradshaw

James Bradshaw works for an international consulting firm based in Dublin, and has a background in journalism and public policy. Outside of work, he writes for a number of publications, on topics including politics, history, culture, film and literature.