We look back at the classical world and classical civilization with glasses that are a little too rose-tinted. Myths were at the foundation of that world – myths about men as well as myths about gods. Myths are still at the foundations of our conception of that world.

Mary Beard, Professor of Classics in Cambridge, in her new work, SPQR: a History of Ancient Rome, prefaces the book by emphasising how ancient Rome is still important. She certainly convinces us. But there are many things that are important but boring. Boring, Rome is emphatically not. This is a fascinating book for all sorts of reasons and on all sorts of levels. One of Beard’s achievements in S.P.Q.R. is to unravel those myths for us and to puncture our own mythical conceptions about the events and the heroes of that time.

It is that rare thing, scholarly and readable, learned and light. It is a joy to read and a magnificent stimulus for reflection on both the origins and development of our own civilization as well as on the perennial threats to its survival which are active in our contemporary world.

This book will not endear you to the Romans, it may even horrify you. It is not that there were not people there trying to do their best, striving for some kind of justice. There were. One of the abiding impressions you get from the book is a sense of mankind’s long, painstaking and faltering journey towards the rule of law in our world.

But one of the questions which haunts us as we make our way through this revision of our cosy and benign view of the Roman world is this: what would our modern world be like today if the radical revolution which was the conversion of this world to Christianity had not taken hold?

Richard Dawkins – in one of his wiser reflections some years ago, in the middle of a diatribe against the Christian Faith – expressed some concern about what might replace Christianity if his wishes for it came true. Well he might, given some of the evidence we have from mankind’s more recent efforts to create godless utopias.

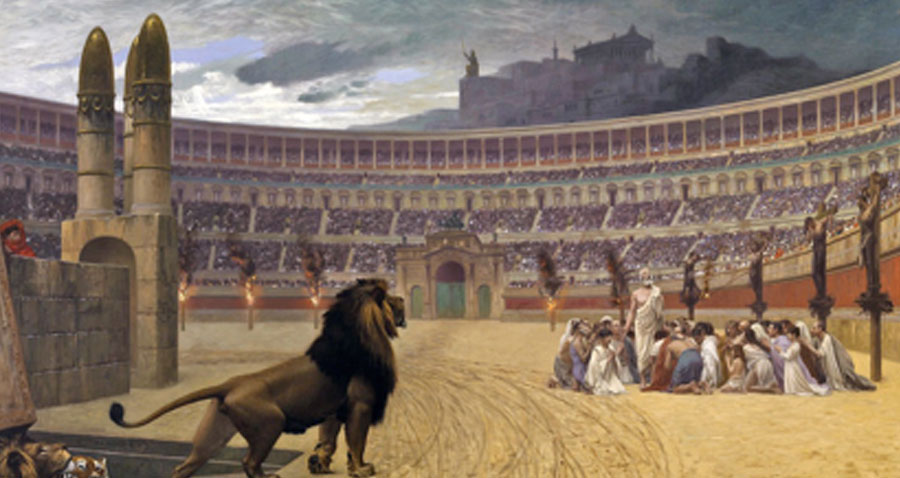

The thought which this book prompts, however, is even more radical. What kind of civilization could faltering mankind ever have achieved had it not been for the emergence of the Christian Faith to take centre-stage in that evolution. The Roman world, even with its ameliorating Greek influences, was devoid of the radical goodness which the Christian message holds. While classical civilization had elements which that message was capable of taking and transforming, it could never have produced that transformation from within its own resources.

Mary Beard helps us to look back to this world with a cold eye and there we see what a floundering and inhumane world it was in which to live. This world was truly alien to the spirit of the subsequent ages, even in their rawest expressions, a spirit which followed the leavening of the mass by Christianity.

Beard’s narrative approach is very different from what we are used to in the writing of ancient history. While the approach is generally chronological she deliberately eschews the tracing of cause and effect in the story. She concentrates instead on giving us insights into the mentality of the people, the life-style and the mores prevailing over her thousand year span. In this we do not get blow by blow accounts of political or military action but a real feel for how political life worked in a militarised state – or did not – as well as what it was like to be a family, a mother, a child in that world.

She recounts the attitude to and the fate of children in the womb: “One letter, surviving on papyrus from Roman Egypt, written by a husband to his pregnant wife, instructs her to raise the child if it is a boy, but ‘if it is a girl, discard it’. How often this happened, and what the exact ratio of the victims was, is a matter of conjecture, but it was often enough for rubbish tips to be thought of as a source of free slaves.” Was this the ancient world’s version of Planned Parenthood (capitals deliberate)? Is there not just a little more than an echo of this in the current controversies surrounding that American state-funded organization?

As for poverty and destitution, the Roman world was truly dark. The sources don’t give a great deal of evidence. The reason for that, Beard tells us, is clear. “First, those who have nothing leave very few traces in the historical or archaeological record. Ephemeral shanty towns do not leave a permanent imprint in the soil; those buried in unmarked graves tell us much less about themselves than those accompanied by an eloquent epitaph. But second, and even more to the point, extreme poverty in the Roman world was a condition that usually solved itself: its victims died.” What there was by way of some social provision for the needy, the “corn dole”, was for the needy within a “privileged group of about 250,000 male citizens in the first and second centuries CE.”

No one in the Roman world, she tells us, “seriously believed that poverty was honourable – until the growth of Christianity…. The idea that a rich man might have a problem entering the kingdom of heaven would have seemed as preposterous to those hanging out in our Ostian bar as to the plutocrat in his mansion.”

Political life operated in a pretty brutal and murderous way. Family life would have had its moments but was a very different reality from what we think of as ideal family life today. It may have taken centuries, even a millennium or more for much of what we experience today to become the norm for us, but we should have no illusions about where it all began. Its beginning is to be found in the words of Christ, “suffer little children to come unto me…”, and in the articulation of Christ’s teaching in the words of St Paul about husbands loving their wives, wives loving their husbands, the sanctity of marriage, and much else.

What shocks us not a little in reading this book is the realization that although we see some of the elements of our own civilization in the world Beard lays before us, we realize how radical and necessary was the peaceful Christian revolution to bring us from there to where we are today. It also helps us ask ourselves the question – what will we lose if we abandon the principles of that revolution as the West is now doing wholesale? It was not until Roman society began to be impregnated by the values of the Judaeo-Christian ethic that the Roman world and Roman law flourished as the framework for western civilisation.

Christians have not always lived up to the standards set by Christ. Benedict XVI has often stressed that profound changes in institutions and people are usually the result of the saints, not of the learned or powerful: “Amid the vicissitudes of history, it has been the saints who have been the true reformers, who have so often lifted mankind out of the dark valleys into which it constantly runs the risk of sinking back again and have brought light whenever necessary.”

So it was in Rome. As Beard recounts in the conclusion of her book, “after periods of coordinated persecution of the Christians in the later third century CE, the universal empire decided to embrace the universal religion (or vice versa). The emperor Constantine…, the first Roman emperor to formally convert to Christianity was baptised on his deathbed. Constantine did, in a way, follow the Augustan model of building himself into power, but what he built was churches.” Her narrative ends just before that event, with the reign of Caracalla.

Casting this kind of a cold eye on Rome is not to denigrate it. It is just important to tell it as it is, as it was. Beard concludes: “We do a disservice to the Romans if we heroise them, as much as if we demonise them. But we do ourselves a disservice if we fail to take them seriously – and if we close our long conversation with them.” We might add that knowing the truth about what we have left behind us is important as an incentive to help us to maintain and treasure what we have. Part of the value of this book is that it does just that.

Addendum

George Weigel wrote in a post on Easter in First Things this week:

The grittiness of Lent, and the “intransigent historical claims” without which Easter makes no sense at all, should remind us that Christianity does not rest on myths or “narratives,” but on radically changed human lives whose effect on their times are historical fact. Within two and a half centuries, what began as a ragtag gang of nobodies from the civilizational outback had so transformed the Mediterranean world that the most powerful man in that world, the Roman emperor Constantine, joined the winning side. How did that happen?

It didn’t happen because of better myth-making. It happened because those first Christians met a young rabbi who promised that, should they believe in him, each of them would become “a spring of water welling up to eternal life” [John 4.14]. Then came what seemed complete catastrophe: his crucifixion. But they met that teacher again as the Risen Lord Jesus Christ, and were infused by his Spirit. And after that, they didn’t sit around in the “presence of the question mark; rather, they told the truth of what they had “seen and heard” [cf. 1 John 1.1].

And thereby changed the world.