For most of the time ordinary people don’t want power. They just want to get on with their lives. Democracy relieved them of dictatorial, aristocratic and oligarchic abuses of power. In our democratic age we expect that all we have to do is choose, every few years, reasonable, just and capable people to look after our public affairs for us – and all will be well. That seems to be enough power to keep us going.

But something radical has now happened. We do not seem to be in this comfortable place anymore.

David Brooks reflected on “powerlessness” in a recent column in the New York Times. He related it to an essay by George Orwell reflecting on an incident in his time as a colonial policeman in Burma back in the 1930s.

“In his essay”, Brooks tells us, “nobody feels like they have any power. The locals, the imperial victims, sure didn’t. Orwell, the guy with the gun, didn’t feel like he had any. The imperialists back in London were too far away.” He thinks this is the way much of the world is today, with everyone afflicted with a widespread sentiment that power is somewhere other than where you are.

Suddenly, we are not so sure that anything we think, say or do matters anymore. If it did why do I have to suppress this sense of fear and loathing every morning as I make my way to work past the Irish parliament buildings?

Brooks, writing in the American context, speaks of the confusion he sees right across the social and political spectrum where every group feels it is being hard done by in the system. A Pew Research Center poll asked Americans, “Would you say your side has been winning or losing more?” Sixty-four percent of Americans, with majorities of both parties, believe their side has been losing more.

Taking this in an Irish context, some people afflicted by this “powerlessness” syndrome say “a plague on all your houses”. Over the past few years they have decided to abandon old party loyalties, support new ones or simply place their trust in “lone ranger” independent representatives.

Others despair even of that when they look at the options that new fledgling parties provide. Still others just look on this as a vain hope, convinced that what they see as a mildly to severely corrupt political and media establishment will manipulate the system no matter who they choose. They just feel helpless in the face of a system which should be guaranteeing them a voice and freedom but which is instead taking their country away from them.

Brooks thinks that the feeling of absolute powerlessness can corrupt absolutely: “As psychological research has shown, many people who feel powerless come to feel unworthy, and become complicit in their own oppression. Some exaggerate the weight and size of the obstacles in front of them. Some feel dehumanized, forsaken, doomed and guilty.”

He believes that the ultimate stand of the hopeless is a defiant but pointless one, and is made when they feel overwhelmed by isolation and atomization. Having lost all trust in their own institutions, they respond to powerlessness with pointless acts of self-destruction. Brooks cites what is happening in the Palestinian territories as a classic example. “Young people don’t organize or work with their government to improve their prospects. They wander into Israel, try to stab a soldier or a pregnant woman and get shot or arrested – every single time. They throw away their lives for a pointless and usually botched moment of terrorism.”

In the United States today, on a macro level, everyone seems to be scratching their heads and asking themselves how this particular electoral cycle leading to the election of their forty-fifth President got so crazy. On a micro level they are agonizing over the strange dysfunction of their legal and law enforcement system which two Columbia University journalism graduates have exposed in their riveting documentary series on Netflix, Making a Murderer.

For Brooks the first is a perversion brought about by feelings of powerlessness. As regards the second, no one seems to have any answers. It all ends up compounding the despair.

Brooks sums up the American dilemma: “Americans are beset by complex, intractable problems that don’t have a clear villain: technological change displaces workers; globalization and the rapid movement of people destabilize communities; family structure dissolves; the political order in the Middle East teeters, the Chinese economy craters, inequality rises, the global order frays, etc.”

Irish citizens seldom agonize over all of these issues – because they don’t expect their chosen representatives to have to deal with them. Our hapless and helpless representatives had to rely on an international troika of the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank to dig it out of the mess they let the country fall into in the mid 2000s. The smug way in which the current political establishment now claims credit for the troika’s vigilance in having guided us to a reasonably safe haven fools some but angers others.

Is Ireland safe from the horrors of the unsafe verdicts and law enforcement shenanigans portrayed in Making a Murder? Irish radio recently spent some time debating whether the dreadful scenario presented in the series could happen in their blessed land. Indeed it could – and from time to time there have been suspicious signs that something like it has.

On the political front, thirty-eight percent of the Irish electorate looked on in dismay last year as a united phalanx of political and media forces, supported by overseas neo-colonial cultural power-houses like Amnesty International and Atlantic Philantrophies, effectively consigned the already badly wounded natural institution of marriage to the rubbish heap of history by effectively redefining it out of existence. Two years earlier the same coordinated forces took the first step in removing from Ireland’s laws and constitution the right to life of unborn children.

The same international coalition is now building up forces again to complete this work and get Ireland to join the world club of states which judicially take the lives of millions of innocent human beings every year. Ireland’s legislators will do this again with the help of hand-picked lackeys to form “expert groups” and “citizen forums”, the modern equivalent of the packed juries of former times which put the veneer of justice on the killing carried out at the behest of their masters.

The citizens who see these developments as catastrophes feel as powerless as victims confronted by an alien force from they know not where. Their fear is compounded by the fact that this force comes in the form of a human agency whose framework of values is totally at odds with everything they know about human nature, human dignity and natural justice. They no longer speak the same language of humanity.

The consequences of this are the slaughter of the unborn, the termination of lives considered “limited”, whether youthful or aged, the destruction of family and the redefinition of human nature itself by the adoption of a crazy gender ideology.

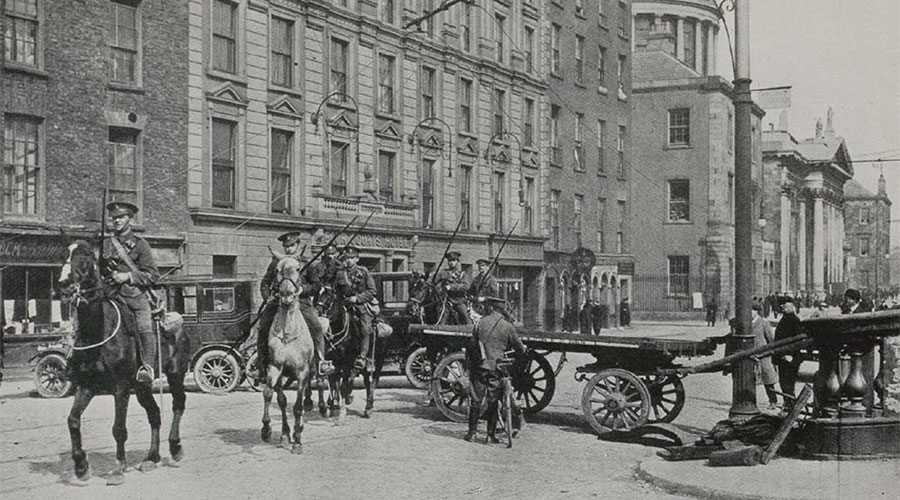

Some but not all of these things have arrived in Ireland. But they surely will and the feeling of powerlessness to do anything about it in the face of an entrenched alien force is breeding despair. How ironic is this in the very year in which Ireland’s people “celebrate” the centenary of the rebellion which led to their winning independence from Britain?

For more than 700 years Ireland was subject to the British Crown. For much of three centuries of that era, up to the later part of the 18th Century, her people suffered bitter and lethal persecution for adhering to the principles of their Catholic Faith. There are many who now fear that the Irish political and media establishment’s adherence to new definitions of humanity contrary to their Faith will usher in a new era of persecution.

In looking for a solution to the problem in his country Brooks argues:

If we’re to have any hope of addressing big systemic problems we’ll have to repair big institutions and have functioning parties and a functioning Congress. We have to discard the anti-political, anti-institutional mood that is prevalent and rebuild effective democratic power centres.

So it may be for America. In the Irish context are new parties the answer? It is doubtful that they are. Why? Because none of these parties have anything of the vision of mankind which would enable them to frame consistent policies – social, political or economic. Without this vision – and the truth about humanity which underlies it – they will never meet the needs of our nature and the hopes and aspirations which arise from that nature.

Some individuals within these movements have such a vision. But these are dismissed by the establishment as “sanctimonious” dreamers. These are the only hope that the powerless have. The fact is that there is no coherent collective voice in evidence yet which might convince the powerless that they might hope to have, even in the future, a government by which their country might be wisely and justly governed.

Until this vision permeates those currently hollow shells which pass for policies, any new solution to their powerlessness will be fruitless. Until then the political and moral bankruptcy of our time will continue to corrupt and thwart the aspirations of those who set the Republic of Ireland up as an independent state nearly 100 years ago.

———

About the Author: Michael Kirke

Michael Kirke is a freelance writer, a regular contributor to Position Papers, and a widely read blogger at Garvan Hill (www.garvan.wordpress.com). His views can be responded to at mjgkirke@gmail.com.